Quantifying Quicksilver

THE ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS of mercury have been known for a long time, and for decades the ubiquitous element has been closely monitored in aquatic environments where it can “bioaccumulate” in fish and other species. But until recently very little was known about how and in what specific form the heavy metal – also known as “quicksilver” – wafted through the atmosphere before being deposited on land or in waters.

Today, thanks to sophisticated instruments that can sniff out mercury and measure it in its various forms – gaseous elemental, reactive, and particulate-phase – a window into the chemical cycling of mercury in the atmosphere is being opened ever wider.

Indeed, a United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) treaty to control global mercury emissions is slated to be forged in 2013 and, in the United States, efforts are underway to create of a national, coordinated network of long-term atmospheric mercury monitoring sites.

If and when these efforts come to pass, the Climate Change Research Center (CCRC), and specifically its AIRMAP program, will be poised to take an active role. AIRMAP has been building a mercury monitoring program for the last six years and is today gathering mercury data with funding from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the National Science Foundation, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to the tune of $2.33 million in total.

“Basically, we’re looking at this issue in different settings and on different scales – from aircraft measuring tropospheric mercury across the Arctic to Appledore Island off the coast of New Hampshire where we’re investigating the marine boundary layer chemistry in great detail,” says CCRC director Robert Talbot. “We’re the only group in the U.S. studying the mercury issue from the regional to global scale.”

Talbot’s research group, which includes research associate professor Huiting Mao, post-doctoral researcher Jeff Sigler, Ph.D. students Su Youn Kim, Dara Feddersen, and Melissa Smith, and CCRC project director Kevan Carpenter, is also conducting mercury research in the Pacific region as well as looking at global-scale implications. All of which means the team is well positioned to take part in an ever-increasing scientific focus on mercury. (See story on the specific AIRMAP mercury monitoring efforts, “At the Head of the Pack.”)

Last summer Talbot and Mao both made presentations at the 9th International Conference on Mercury as a Global Pollutant (ICMGP) in Guiyang, China. Held periodically for over the last 18 years, the conference has become the preeminent international forum where the mercury concerns of the developed and developing worlds are shared – and formal presentations and discussions of the scientific advances concerning environmental mercury are conducted.

In the span of nearly two decades, the depth, breadth, and pace of scientific discoveries on the sources, environmental transport and fate, biogeochemical cycling, and adverse effects of mercury have increased enormously since the inaugural conference was convened in Sweden in 1990.

Concurrent with this scientific knowledge has been the rapid economic growth and industrial development in countries such as China, India, and Brazil, which have become major mercury emitters in the world and as such have drawn more attention from the scientific community as well as national governments.

While in China, Talbot and Mao began exploring a potential collaboration with faculty at the School of Atmospheric Sciences at Nanjing University to establish a mercury monitoring station. The site will be located on top of a 25-story building on the campus located in central Nanjing. This would be the first mercury monitoring site in the heavily urbanized and industrialized coal-burning region of eastern China.

Mao notes that when this additional monitoring site is established in Nanjing it will extend AIRMAP’s reach and “we will be well positioned to be part of a global network of mercury monitoring sites.”

Says Talbot, “In terms of atmospheric chemistry and dynamics, this is such a new area of research that we don’t have long-term data” without which effective policy cannot be crafted. “We can now measure how much is in the atmosphere but what you really want to do is measure what’s going in and out – you need to know the sources and sinks of mercury in all its forms.”

Like NOAA’s Climate Reference Network – 114 stations across the continental U.S. designed to detect the national signal of climate change by using identical instrumentation – the Atmospheric Mercury Monitoring Services network operated by the U.S. EPA likewise gathers mercury data from select sites across the nation using identical instruments and methods. (AIRMAP’s Thompson Farm observatory is part of both the EPA mercury network and NOAA’s climate network.) Such an accurate, long-term dataset will provide a clear picture of mercury’s cycling through the environment, which in turn will be used to craft effective policy.

“You wouldn’t want to spend a billion dollars to reduce mercury emissions from coal-fired plants only to find out that the world’s oceans are the largest source. We need to be able to put accurate numbers on the sources,” Talbot explains. -DS

Today, thanks to sophisticated instruments that can sniff out mercury and measure it in its various forms – gaseous elemental, reactive, and particulate-phase – a window into the chemical cycling of mercury in the atmosphere is being opened ever wider.

|

|

| Precipitation collectors for measuring wet-deposition mercury. The prongs on top discourage birds from perching.Photo by K.Carpenter, UNH-EOS. |

If and when these efforts come to pass, the Climate Change Research Center (CCRC), and specifically its AIRMAP program, will be poised to take an active role. AIRMAP has been building a mercury monitoring program for the last six years and is today gathering mercury data with funding from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the National Science Foundation, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to the tune of $2.33 million in total.

“Basically, we’re looking at this issue in different settings and on different scales – from aircraft measuring tropospheric mercury across the Arctic to Appledore Island off the coast of New Hampshire where we’re investigating the marine boundary layer chemistry in great detail,” says CCRC director Robert Talbot. “We’re the only group in the U.S. studying the mercury issue from the regional to global scale.”

|

|

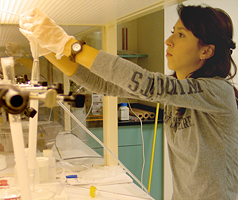

| Graduate student Dara Feddersen coats glassware with a salt solution for stripping out oxidized mercury. Photo by D.Sims, UNH-EOS |

Last summer Talbot and Mao both made presentations at the 9th International Conference on Mercury as a Global Pollutant (ICMGP) in Guiyang, China. Held periodically for over the last 18 years, the conference has become the preeminent international forum where the mercury concerns of the developed and developing worlds are shared – and formal presentations and discussions of the scientific advances concerning environmental mercury are conducted.

In the span of nearly two decades, the depth, breadth, and pace of scientific discoveries on the sources, environmental transport and fate, biogeochemical cycling, and adverse effects of mercury have increased enormously since the inaugural conference was convened in Sweden in 1990.

Concurrent with this scientific knowledge has been the rapid economic growth and industrial development in countries such as China, India, and Brazil, which have become major mercury emitters in the world and as such have drawn more attention from the scientific community as well as national governments.

While in China, Talbot and Mao began exploring a potential collaboration with faculty at the School of Atmospheric Sciences at Nanjing University to establish a mercury monitoring station. The site will be located on top of a 25-story building on the campus located in central Nanjing. This would be the first mercury monitoring site in the heavily urbanized and industrialized coal-burning region of eastern China.

Mao notes that when this additional monitoring site is established in Nanjing it will extend AIRMAP’s reach and “we will be well positioned to be part of a global network of mercury monitoring sites.”

Says Talbot, “In terms of atmospheric chemistry and dynamics, this is such a new area of research that we don’t have long-term data” without which effective policy cannot be crafted. “We can now measure how much is in the atmosphere but what you really want to do is measure what’s going in and out – you need to know the sources and sinks of mercury in all its forms.”

Like NOAA’s Climate Reference Network – 114 stations across the continental U.S. designed to detect the national signal of climate change by using identical instrumentation – the Atmospheric Mercury Monitoring Services network operated by the U.S. EPA likewise gathers mercury data from select sites across the nation using identical instruments and methods. (AIRMAP’s Thompson Farm observatory is part of both the EPA mercury network and NOAA’s climate network.) Such an accurate, long-term dataset will provide a clear picture of mercury’s cycling through the environment, which in turn will be used to craft effective policy.

“You wouldn’t want to spend a billion dollars to reduce mercury emissions from coal-fired plants only to find out that the world’s oceans are the largest source. We need to be able to put accurate numbers on the sources,” Talbot explains. -DS

by David Sims, Science Writer, Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space. Published in Fall 2009 issue of EOS .