Lose 10,000 Pounds, Lighten Your Footprint

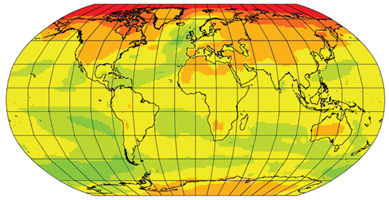

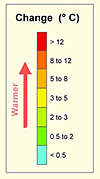

A FEW YEARS AGO, Denise Blaha of the Complex Systems Research Center was working with data from the National Center for Atmospheric Research and the 2007 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Assessment to create climate visualization maps. Looking at the maps scared her right out of her seat.

Recalls Blaha, “In those maps I was seeing a drastically different planet and, suddenly, my climate change work became more than a professional activity, it became a personal concern. I was looking at a world my daughter could potentially be living in.” In the gloomiest of scenarios it was a hot world of catastrophic change.

So she immediately began a personal campaign to lower her family’s carbon footprint, and then took the nascent effort on the road. She gave half a dozen talks to local groups about relatively modest steps average people can take to help save the planet – change to compact fluorescent light bulbs, drive a fuel-efficient car, drive less, hang clothes out to dry, etc. “I was shocked to discover you could actually do a lot,” Blaha says.

After her talks she discovered other people, too, were shocked – both at the climate projections she presented and the modest efforts that, collectively, could fuel huge carbon emission reductions in the residential sector. One of those people was Julia Dundorf, a mother of three and business owner who had asked Blaha to bring her message to a local group of women.

“Julia and many of the other women in the audience were so disturbed by the projected impacts of climate change that they decided to do something about it individually and as a group,” Blaha says. Dundorf joined forces with Blaha bringing skills in activism and networking to Blaha’s scientific expertise and passion to make a difference.

Says Dundorf, “We had such a terrific response from this group that we decided to give a few more talks around seacoast New Hampshire and were soon inundated with speaking requests.”

The inundation eventually led to the creation of the New Hampshire Carbon Challenge – co-directed by Blaha and Dundorf and financed with seed funding from the Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space.

The chief tool of the Carbon Challenge is a web-based carbon calculator called the New England Carbon Estimator™. With it, homeowners identify actions they can take in their homes to reduce energy consumption, costs, and greenhouse gas emissions. Based upon those actions the tool estimates potential savings tailored to that specific household. This process, which takes only 10 to 15 minutes to complete, is “Taking the Challenge.”

Two years after its humble beginnings, the Carbon Challenge has exceeded the wildest expectations. To wit: the program was selected as the residential outreach component of the recently unveiled New Hampshire Climate Action Plan, and in May it became a joint initiative with Clean Air-Cool Planet – a regional, science-based, non-profit organization dedicated to finding and promoting solutions to global warming. The merger will broaden the program’s reach beyond New Hampshire and towns in bordering states to the entire New England region, the Northeast, and, eventually, across the nation.

Announcing the new partnership, Adam Markham, CEO of Clean Air-Cool Planet, said “This collaboration allows both Clean Air-Cool Planet and UNH to better serve our respective and common constituencies.”

“The New Hampshire Carbon Challenge still exists,” explains Blaha, “but it’s now the first state initiative in what we’re calling the Residential Carbon Challenge – the larger umbrella organization in collaboration with Clean Air-Cool Planet.” Under the merger Dundorf became Clean Air - Cool Planet’s manager of community relations.

Because nearly half of all greenhouse gas emissions come from residential heating, cooling, electricity, and transportation, the success of the New Hampshire Carbon Challenge, and it’s merger with Clean Air-Cool Planet, is a significant step forward in efforts to combat global warming.

As Blaha notes, while there have been a number of programs and initiatives aimed at controlling greenhouse gas emissions, “historically, the residential sector has been the hardest nut to crack” because it’s difficult to change personal behaviors.

“Our homes are our castles, and we want to drive any car we choose – it’s that sort of thing,” Blaha says.

That the Carbon Challenge has convinced over 2,000 households to pledge carbon reductions totaling 13,500,000 pounds of CO2 for a collective savings of $1.4 million represents some serious cracking of a tough nut.

“We’ve been able to make the connection between energy consumption, emissions, and energy costs, and demonstrate to households that by making some fairly modest changes they can significantly reduce their energy expenses and emissions. I say to people, ‘Give me 15 minutes and I can probably save you several hundred dollars in energy costs.’” Blaha says. Another program catchphrase has been, “Ask me how I lost 10,000 pounds!”

Changes homeowners can pledge to make range from driving less, changing to compact fluorescent light bulbs, recycling, and washing clothes in cold water to purchasing a fuel-efficient car, an Energy Star refrigerator, or using biodiesel fuel instead of home heating oil.

To date, households that have taken the Carbon Challenge have reduced their energy use by an average of 16% and are saving approximately $750 a year in fuel and electricity costs.

According to Blaha, one of the most powerful aspects of the program is that when a household takes the challenge it is always “linked” to other households in town that have done the same (a household can also select to be part of other groups, like businesses, schools, churches or municipalities, who have taken the challenge).

This linkage is visible on the website via a couple of means, including a regional map that identifies every town or business to have taken the challenge along with the associated tally of CO2 reductions and cost savings.

It's pretty clear from social science research that people make environmentally beneficial changes when their friends, families, and neighbors make similar changes,” Blaha says. “Linking households together is a good way for a community to publicize their collective effort and encourage more households to do the same.”-DS

For more on the New England Carbon Challenge visit: http://necarbonchallenge.org.

Recalls Blaha, “In those maps I was seeing a drastically different planet and, suddenly, my climate change work became more than a professional activity, it became a personal concern. I was looking at a world my daughter could potentially be living in.” In the gloomiest of scenarios it was a hot world of catastrophic change.

So she immediately began a personal campaign to lower her family’s carbon footprint, and then took the nascent effort on the road. She gave half a dozen talks to local groups about relatively modest steps average people can take to help save the planet – change to compact fluorescent light bulbs, drive a fuel-efficient car, drive less, hang clothes out to dry, etc. “I was shocked to discover you could actually do a lot,” Blaha says.

| Denise Blaha and Julia Dundorf Photo by K. Donahue, UNH-EOS |

“Julia and many of the other women in the audience were so disturbed by the projected impacts of climate change that they decided to do something about it individually and as a group,” Blaha says. Dundorf joined forces with Blaha bringing skills in activism and networking to Blaha’s scientific expertise and passion to make a difference.

Says Dundorf, “We had such a terrific response from this group that we decided to give a few more talks around seacoast New Hampshire and were soon inundated with speaking requests.”

The inundation eventually led to the creation of the New Hampshire Carbon Challenge – co-directed by Blaha and Dundorf and financed with seed funding from the Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space.

The chief tool of the Carbon Challenge is a web-based carbon calculator called the New England Carbon Estimator™. With it, homeowners identify actions they can take in their homes to reduce energy consumption, costs, and greenhouse gas emissions. Based upon those actions the tool estimates potential savings tailored to that specific household. This process, which takes only 10 to 15 minutes to complete, is “Taking the Challenge.”

Two years after its humble beginnings, the Carbon Challenge has exceeded the wildest expectations. To wit: the program was selected as the residential outreach component of the recently unveiled New Hampshire Climate Action Plan, and in May it became a joint initiative with Clean Air-Cool Planet – a regional, science-based, non-profit organization dedicated to finding and promoting solutions to global warming. The merger will broaden the program’s reach beyond New Hampshire and towns in bordering states to the entire New England region, the Northeast, and, eventually, across the nation.

|

|

Announcing the new partnership, Adam Markham, CEO of Clean Air-Cool Planet, said “This collaboration allows both Clean Air-Cool Planet and UNH to better serve our respective and common constituencies.”

“The New Hampshire Carbon Challenge still exists,” explains Blaha, “but it’s now the first state initiative in what we’re calling the Residential Carbon Challenge – the larger umbrella organization in collaboration with Clean Air-Cool Planet.” Under the merger Dundorf became Clean Air - Cool Planet’s manager of community relations.

Because nearly half of all greenhouse gas emissions come from residential heating, cooling, electricity, and transportation, the success of the New Hampshire Carbon Challenge, and it’s merger with Clean Air-Cool Planet, is a significant step forward in efforts to combat global warming.

As Blaha notes, while there have been a number of programs and initiatives aimed at controlling greenhouse gas emissions, “historically, the residential sector has been the hardest nut to crack” because it’s difficult to change personal behaviors.

“Our homes are our castles, and we want to drive any car we choose – it’s that sort of thing,” Blaha says.

That the Carbon Challenge has convinced over 2,000 households to pledge carbon reductions totaling 13,500,000 pounds of CO2 for a collective savings of $1.4 million represents some serious cracking of a tough nut.

“We’ve been able to make the connection between energy consumption, emissions, and energy costs, and demonstrate to households that by making some fairly modest changes they can significantly reduce their energy expenses and emissions. I say to people, ‘Give me 15 minutes and I can probably save you several hundred dollars in energy costs.’” Blaha says. Another program catchphrase has been, “Ask me how I lost 10,000 pounds!”

Changes homeowners can pledge to make range from driving less, changing to compact fluorescent light bulbs, recycling, and washing clothes in cold water to purchasing a fuel-efficient car, an Energy Star refrigerator, or using biodiesel fuel instead of home heating oil.

To date, households that have taken the Carbon Challenge have reduced their energy use by an average of 16% and are saving approximately $750 a year in fuel and electricity costs.

According to Blaha, one of the most powerful aspects of the program is that when a household takes the challenge it is always “linked” to other households in town that have done the same (a household can also select to be part of other groups, like businesses, schools, churches or municipalities, who have taken the challenge).

This linkage is visible on the website via a couple of means, including a regional map that identifies every town or business to have taken the challenge along with the associated tally of CO2 reductions and cost savings.

It's pretty clear from social science research that people make environmentally beneficial changes when their friends, families, and neighbors make similar changes,” Blaha says. “Linking households together is a good way for a community to publicize their collective effort and encourage more households to do the same.”-DS

For more on the New England Carbon Challenge visit: http://necarbonchallenge.org.

by David Sims, Science Writer, Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space. Published in Fall 2009 issue of EOS .