From the Lamprey to the Beltway, Again

ERIKA WASHBURN found her way to the Ocean Process Analysis Laboratory at EOS by way of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency where, in 2002, she was working in the Ocean and Coastal Protection Division. Washburn happened to hear fisheries expert Andrew Rosenberg, who at the time was dean of the UNH College of Life Sciences and Agriculture, give a talk to a D.C. audience on work of the U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy.

The two chatted about Ph.D. programs and, several years later Washburn made her way to OPAL where she concentrated her studies on socio-environmental aspects of coastal watersheds, the Lamprey River watershed in particular.

Now Dr. Washburn, she is returning to Washington on a Dean John Knauss Marine Policy Fellowship – a one-year fellowship sponsored by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Association's (NOAA) Sea Grant College Program.

The fellowship is designed for graduate and post-doctoral students with an interest in marine, ocean, and Great Lakes resources and the national policy decisions affecting them. Washburn will be working in the Executive Branch where she hopes to contribute to policy discussions concerning coastal ecosystem-based management and connections with land use in coastal watersheds.

Notes Washburn, “The Knauss Fellowship means a great deal to me because I have been interested in policy for coastal and water management ever since I was a Fulbright Scholar ten years ago working in the Netherlands on this same topic. This fellowship gives me an opportunity to learn more about national policy formulation, the coordination between various government offices and agencies, and the role of NOAA and Sea Grant.”

Washburn believes her Ph.D. work will provide her with insight into some of the on-the-ground repercussions that national policy has for coastal management. That is, she says, policy can change behavior and open up opportunities at the federal, state, and local level to improve how decisions related to the ecosystem are made.

“I will definitely arrive in D.C. with a good deal of reflection on what policy developments mean to Great Bay, to New Hampshire seacoast communities, and to the coastal managers working here.”

For her doctorate (Rosenberg, now a professor in OPAL and the Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, was her committee chair), Washburn conducted an intensive socio-environmental study of the Lamprey River watershed in southern/coastal New Hampshire. The Lamprey, which originates in Northwood’s Saddleback Mountains and makes a 47.3 mile journey to Great Bay, encompasses 14 towns, two counties and has a diversity of demographic and ecosystem characteristics.

“I studied the land-use decision-making characteristics made by citizen volunteers – for example, conservation and open-space commissions, zoning and planning boards – in all 14 towns in the watershed,” Washburn says.

Her in-depth, two-hour interviews pulled together a unique array of information about how these commissions and boards made their decisions concerning land-use and, ultimately, if at times unknowingly, how those decisions contributed to watershed issues: where do they get information to make decisions as a group; is information shared between groups commissions/boards; do they talk to other groups in the region; do they talk to upstream/downstream towns; how often does the impact to Great Bay and the coastal ocean come up in conversation; and what types of local policy have the towns enacted in terms of “smart growth” or innovative land-use planning – do they consider sprawl in their discussions, or do they talk about cumulative impacts of impervious surface areas?

“I was probing to see if and how they were thinking ‘spatially’ in terms of making decisions that have long-term impact,” Washburn explains. She found that, in fact, “most people aren’t used to thinking in spatial scales or thinking of cumulative impacts over the entire watershed.”

She adds that her “semi-structured” interviews were designed to elicit “stories, real details about what people have experienced. I heard a lot of vented frustrations, and that’s probably a good example of the problem of administrative boundaries crisscrossing an ecosystem.”

The greatest aid in eliciting details from people was her use of GIS maps of various portions of the Lamprey watershed. For the maps, Washburn used existing New Hampshire Geographically Referenced Analysis and Information Transfer System (GRANIT) data layers and designed a unique set of GIS-based maps for her interviews. This visual aid allowed people to see on a spatial scale and to “brainstorm” better about potential long-term, cumulative impacts from land-use decisions.

“The maps really help foster discussion. People can see the impervious surface layers building up and we talk about how all these land-use decisions ultimately affect the downstream towns,” she says. “And you can scale it up from the Lamprey to the Piscataqua River and coastal watershed – it’s the same story. Cumulative land-use impacts affect everything in the coastal area, everything downstream, not just water quality and quantity,” Washburn emphasizes. For example, when impervious surfaces (roads, parking lots) cover eight to 10 percent of a watershed that is typically the “tipping point” in terms of water quality.

Although she will begin anew with other, higher-level projects in Washington, she believes her Ph.D. will live on, with any luck.

“One of my ultimate goals in this work was to create a methodology that can be used anywhere to map out where communities are in terms of thinking spatially about a watershed ecosystem. And, hopefully, this will help move them towards a more ecosystem-based form of management and a watershed master planning program rather than just a town-by-town plan,” she says.

Indeed, in part as a result of her research, there is gathering momentum to move these efforts forward and, in June, some 80 people convened for the first Lamprey watershed, 14-town-wide meeting held to discuss land-use planning.

“So I feel pretty good about the prospects here,” Washburn says adding, “and at the recent NOAA Coastal Zone 09 conference in Boston, there was also a lot of interest in my methodology, so I hope to get the word out through publications, webinars and speaking events.”

Another bright note, Washburn points out, is that last summer President Obama established an Interagency Ocean Policy Task Force under the White House Council on Environmental Quality to develop a national policy for the oceans, coasts and Great Lakes, a framework for policy coordination, and an implementation strategy to move forward with the recommendations of the U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy. (OPAL’s Andrew Rosenberg, who also served on the Commission on Ocean Policy, was tapped by the White House to be an advisor to the Interagency Ocean Policy Task Force for the balance of 2009.)

“There are some discussions underway about how to link this framework with land use in coastal and inland watersheds and this is an area in which I would love to have an opportunity to contribute,” says Washburn. -DS

The two chatted about Ph.D. programs and, several years later Washburn made her way to OPAL where she concentrated her studies on socio-environmental aspects of coastal watersheds, the Lamprey River watershed in particular.

|

Erika Washburn

Photo by D.Sims, UNH-EOS |

The fellowship is designed for graduate and post-doctoral students with an interest in marine, ocean, and Great Lakes resources and the national policy decisions affecting them. Washburn will be working in the Executive Branch where she hopes to contribute to policy discussions concerning coastal ecosystem-based management and connections with land use in coastal watersheds.

Notes Washburn, “The Knauss Fellowship means a great deal to me because I have been interested in policy for coastal and water management ever since I was a Fulbright Scholar ten years ago working in the Netherlands on this same topic. This fellowship gives me an opportunity to learn more about national policy formulation, the coordination between various government offices and agencies, and the role of NOAA and Sea Grant.”

Washburn believes her Ph.D. work will provide her with insight into some of the on-the-ground repercussions that national policy has for coastal management. That is, she says, policy can change behavior and open up opportunities at the federal, state, and local level to improve how decisions related to the ecosystem are made.

“I will definitely arrive in D.C. with a good deal of reflection on what policy developments mean to Great Bay, to New Hampshire seacoast communities, and to the coastal managers working here.”

For her doctorate (Rosenberg, now a professor in OPAL and the Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, was her committee chair), Washburn conducted an intensive socio-environmental study of the Lamprey River watershed in southern/coastal New Hampshire. The Lamprey, which originates in Northwood’s Saddleback Mountains and makes a 47.3 mile journey to Great Bay, encompasses 14 towns, two counties and has a diversity of demographic and ecosystem characteristics.

“I studied the land-use decision-making characteristics made by citizen volunteers – for example, conservation and open-space commissions, zoning and planning boards – in all 14 towns in the watershed,” Washburn says.

Her in-depth, two-hour interviews pulled together a unique array of information about how these commissions and boards made their decisions concerning land-use and, ultimately, if at times unknowingly, how those decisions contributed to watershed issues: where do they get information to make decisions as a group; is information shared between groups commissions/boards; do they talk to other groups in the region; do they talk to upstream/downstream towns; how often does the impact to Great Bay and the coastal ocean come up in conversation; and what types of local policy have the towns enacted in terms of “smart growth” or innovative land-use planning – do they consider sprawl in their discussions, or do they talk about cumulative impacts of impervious surface areas?

“I was probing to see if and how they were thinking ‘spatially’ in terms of making decisions that have long-term impact,” Washburn explains. She found that, in fact, “most people aren’t used to thinking in spatial scales or thinking of cumulative impacts over the entire watershed.”

She adds that her “semi-structured” interviews were designed to elicit “stories, real details about what people have experienced. I heard a lot of vented frustrations, and that’s probably a good example of the problem of administrative boundaries crisscrossing an ecosystem.”

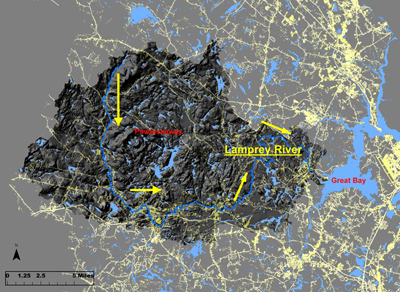

Lamprey River and watershed with impervious surface areas (yellow).

Map created by Erika Washburn. |

The greatest aid in eliciting details from people was her use of GIS maps of various portions of the Lamprey watershed. For the maps, Washburn used existing New Hampshire Geographically Referenced Analysis and Information Transfer System (GRANIT) data layers and designed a unique set of GIS-based maps for her interviews. This visual aid allowed people to see on a spatial scale and to “brainstorm” better about potential long-term, cumulative impacts from land-use decisions.

“The maps really help foster discussion. People can see the impervious surface layers building up and we talk about how all these land-use decisions ultimately affect the downstream towns,” she says. “And you can scale it up from the Lamprey to the Piscataqua River and coastal watershed – it’s the same story. Cumulative land-use impacts affect everything in the coastal area, everything downstream, not just water quality and quantity,” Washburn emphasizes. For example, when impervious surfaces (roads, parking lots) cover eight to 10 percent of a watershed that is typically the “tipping point” in terms of water quality.

Although she will begin anew with other, higher-level projects in Washington, she believes her Ph.D. will live on, with any luck.

“One of my ultimate goals in this work was to create a methodology that can be used anywhere to map out where communities are in terms of thinking spatially about a watershed ecosystem. And, hopefully, this will help move them towards a more ecosystem-based form of management and a watershed master planning program rather than just a town-by-town plan,” she says.

Indeed, in part as a result of her research, there is gathering momentum to move these efforts forward and, in June, some 80 people convened for the first Lamprey watershed, 14-town-wide meeting held to discuss land-use planning.

“So I feel pretty good about the prospects here,” Washburn says adding, “and at the recent NOAA Coastal Zone 09 conference in Boston, there was also a lot of interest in my methodology, so I hope to get the word out through publications, webinars and speaking events.”

Another bright note, Washburn points out, is that last summer President Obama established an Interagency Ocean Policy Task Force under the White House Council on Environmental Quality to develop a national policy for the oceans, coasts and Great Lakes, a framework for policy coordination, and an implementation strategy to move forward with the recommendations of the U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy. (OPAL’s Andrew Rosenberg, who also served on the Commission on Ocean Policy, was tapped by the White House to be an advisor to the Interagency Ocean Policy Task Force for the balance of 2009.)

“There are some discussions underway about how to link this framework with land use in coastal and inland watersheds and this is an area in which I would love to have an opportunity to contribute,” says Washburn. -DS

by David Sims, Science Writer, Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space. Published in Fall 2009 issue of EOS .