Spring 2014

Earth Systems Science

Until this past February, Barry Rock had no idea that over twenty years of scientific data gathered by students and teachers in UNH's inquiry-based Forest Watch program were a mirror image of crucial environmental findings recently released by state officials.

|

|

| One-hundred-foot-tall white pine by the Soucook River in Loudon, NH. Photo courtesy of Phil Browne. |

Since its founding in 1991, the program's research on white pines around the New England region, which is conducted by K-12 students and their teachers, in conjunction with UNH researchers, has shown a steady increase in the health of this vital forest species.

While the Forest Watch analysis showed the trees' vigor to be tied to improved air quality, it wasn't until Rock saw ozone, or smog, records the state's Department of Environmental Services-Air Resources Division had collected since the late 1980s that the big picture came into focus: steadily declining ozone levels since 1991 fit the year-to-year improvements in white pine health like a glove.

"It was just coincidence that Forest Watch began in 1991, the year of our highest ozone levels as it turns out, but now we know there's no coincidence between lower ozone and improved white pine health," says Rock, the founding director of Forest Watch and now professor emeritus in the Earth Systems Research Center and department of natural resources.

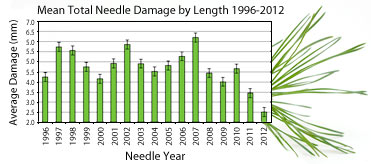

Every year, Forest Watch students and their teachers gather white pine needles from trees near their schools, measure the length of the needles and the amount of area occupied by spots caused by ozone damage—chlorotic mottling, for example—and calculate the percentage area of needle damage. Rock and his researchers also gather comparative data on rainfall, temperature, and insects to see if these might factor into tree health or damage.

Pinus strobus, or the eastern white pine, is a known bio-indicator species for exposure to ground-level ozone—as opposed to the "good" ozone in Earth's upper atmosphere that protects us from ultraviolet radiation.

In addition to damage to new needles, older needles are lost as well when smog levels are high. Thus, during poor air quality years, white pine growth is impaired and results in reduced economic and environmental value of the trees. Ozone reduces a tree's ability to convert sunlight into energy and food and accelerates aging in older foliage.

In 1990, the federal Clean Air Act Amendments took effect and eventually led to the enactment of the state's National Ambient Air Quality Standards in 1997, which Rock characterizes as "the clincher" with respect to falling ozone levels and needles with increased, vigorous growth for longer periods of time.

The manufacture of ground-level ozone requires nitrogen oxides that come out of the tailpipes of cars, as well as both manmade and natural volatile organic compounds from, for example, paint thinners and the active growth of plants. In the presence of sunlight and elevated temperatures, these compounds generate the smog that Forest Watch has tracked for over two decades.

|

|

| Forest watch teacher workshops held at UNH. Photo by Kristi Donahue, UNH-EOS |

Rock notes that, together with federal regulations, the state has been implementing a number of policies that reduce both nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds emitted into the atmosphere.

"I've always maintained that policy changes drive innovation, and here's a great example of federal and state regulations aimed at reducing pollutants, including recent reduced carbon dioxide emission levels, EPA-required improved mileage standards, and more hybrid vehicles on the road, etcetera, having a dramatic, positive impact on air quality and white pine health," Rock says. "And this is a key message to get out to the public because it comes at a time when there is a growing effort in Congress to trim back on EPA regulations, which are considered by some to be too restrictive on business and industry."

Smoke signals

While the 2014 ozone story is a good one, the 2010/11 Forest Watch annual winter meeting reported on a troubling development that, Rock says, "At the time, some gloom and doom news reports suggested white pine might become an endangered species across New England."

The gloom and doom was based on two years of reports from around New England of unusually large numbers of white pine needles piled up along sidewalks and roadways. After analyzing the data, Forest Watch announced that 2010 marked the first time in the program's long history of observations that white pines did not retain important older needles.

"White pines usually keep healthy, green needles that contribute significantly to the photosynthetic process by the whole tree for two or three full years," says Rock. "So something very serious was stressing the trees and resulting a region-wide outbreak of white pine needle cast disease. Not since the early to mid-1990s, when ozone levels were extremely high, have we seen these kinds of measurements of stress in the pines."

More recent samples and measurements made by Forest Watch suggest that a new environmental stressor appeared in spring 2010 and affected old needles that opened in 2008 and 2009. That stressor is now suspected to have been an air pollution event emanating from Canada in May 2010 that defoliated another signature New England tree—the sugar maple.

"We believe that peroxyacetyl nitrate, a powerful oxidant in wildfire smoke, in combination with unusually high temperatures, might have heavily damaged the 2010 maple leaves," Rock says. "The event might also have stressed the 2008 and 2009 pine needles, and other pollutants from a growing number of wildfires might be causing further stress."

|

|

| Close-up of white pine needles. Photo by Martha Carlson, UNH Forest Watch |

Another theory is that unusually wet weather in 2009 caused an explosion of fungi that feasted on the pine needles. In 2010 and 2011, the U.S. Forest Service reported a dramatic increase in the occurrence of several pine needle cast fungi on older needles, and Forest Watch researchers worked with the Forest Service to understand the cause of this dramatic increase in reported cases of needle cast fungus.

At the Forest Watch annual teacher workshop held in early February 2014, Kirk Broders, a mycologist in the UNH department of biological sciences, announced preliminary findings from analysis he's been doing on the white pine needle cast disease using needles collected from across New England by Forest Watch students.

Broders cultivated specific fungi known to cause the disease since 2011-12 and discovered there were many more types of fungi—15 to 18 species—associated with it, including three or four new to science.

According to Broders, while there was a diversity of fungi found infecting white pine needles, only four species, including one of the newly discovered ones, were found in more than two locations.

"We believe that one or a combination of these fungi are responsible for the recent outbreaks of white pine needle damage," Broders says. "It's possible that recent warmer and wetter-than-average climate may be allowing this fungus to spread into the range of the eastern white pine resulting in needle defoliation epidemics. Further monitoring using the Forest Watch network will help us keep tabs on this emerging threat to white pines in our region."

|

|

| Forest Watch student observations. Photo by Martha Carlson, UNH Forest Watch |

|

A core strength of Forest Watch, and one that teachers relish, is its emphasis on current research findings in the STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) disciplines. Broders' findings, Rock notes, are a perfect example of the type of cutting-edge science Forest Watch teachers eagerly share with their students.

Says Rock, "These K-12 students use science—ozone effects on photosynthesis, etcetera— technology—learning about the spectral reflectance properties of pine needles, using Landsat data with freeware image processing software—engineering—making their own measurement tools—and math—calculating percent of needle damage, tree growth rates, and canopy closure—to estimate the health of white pines. So the program provides them with a real soup-to-nuts STEM experience."