Spring 2015

Space Science

UNH senior Chrystal Moser laid the foundation of her future through baby steps

IN DECEMBER OF 2013, Space Science Center associate professor Marc Lessard stepped on a little donut-shaped bead on his daughter's bedroom floor and had a eureka moment.

“Picking it up I realized it was the exact shape and size we needed to begin building the miniature magnetometer for a small satellite project we were working on,” recalls Lessard. “I gave it to my undergraduate research assistant Chrystal Moser and said, ‘Here, take the finest copper wire you can handle, thread it through the hole, and wind and wrap the bead as tightly and thoroughly as you can.’”

Moser accepted the challenge with gusto.

A sophomore physics major at the time, Moser had only recently linked up with Lessard in an effort to get some hands-on undergraduate research experience—very hands-on it turns out. She had worked in the SSC previously doing programming but found that work not to be a good fit, especially with an eye on her future scientific endeavors.

Says Moser, “I’m not a terribly good programmer and felt I needed to be working in a lab doing real hands-on research. When Marc gave me the little bead and said, essentially, go figure out a way to wrap it with copper wire to make a magnetometer, I jumped at the chance.”

Moser didn’t know the first thing about magnetometers—something Lessard, a rocket scientist, specializes in—had taken no courses in electricity or magnetism but relished being there in Lessard’s Magnetosphere-Ionosphere Research Laboratory getting her hands dirty baby step by baby step.

“I was using copper wire about the size of a human hair and winding it on something as small as that bead took me six hours to make 300 turns by hand,” says Moser. She adds, “I actually liked that—I could think my own thoughts and focus on the challenging physical process. I had to learn as I went along, and that was the most fun—having the creative freedom to problem solve, explore.”

Being given the freedom by Lessard to work largely independently (and independently “taking” a self-designed textbook and online course on the workings of magnetometers), Moser’s first challenge was to simply figure out how to physically manage the task at hand—repeatedly threading a wire .0067 of an inch thick through and around a bead the size of a green pea.

At first she tried using a small vice on a lab workbench but found it difficult to manipulate the wire without it breaking. “So I ended up just taping it to a table so I could rotate it as I did the winding, scoot it around easily when starting a new layer of wiring, flip it over, etcetera.”

| |

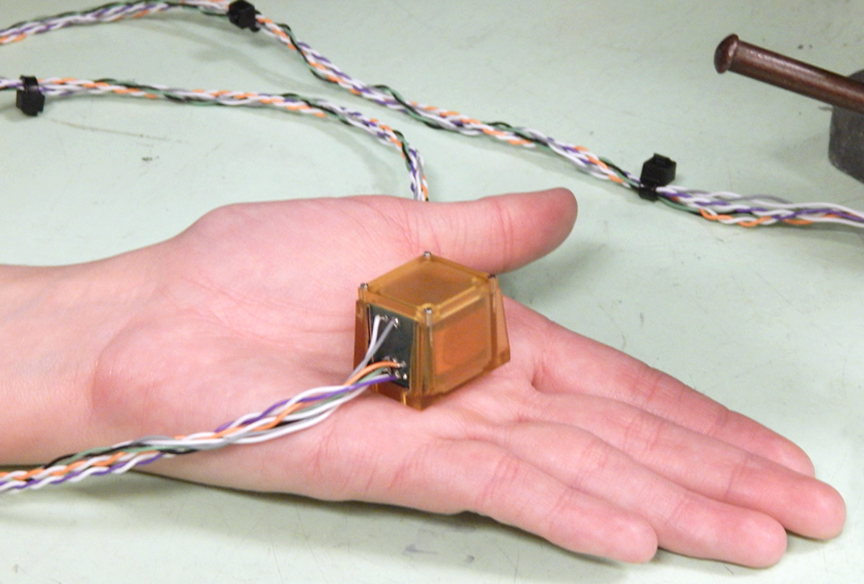

| The miniature magnetometer. Photo by David Sims, UNH-EOS. |

Once she had mastered the technique, the plastic bead was replaced with a tiny bobbin made of a nickel-chromium alloy known as Inconel that was then wrapped with a nickel-iron alloy material and heat treated. It was on this little high-tech gizmo that Moser carefully wrapped the copper wire to create the mini-magnetometer.

The entire magnetometer, which is comprised of two coils of copper wire aligned in opposite directions, a high-tech plastic “doghouse” sheltering the copper coils and a scant electrical connector board is not much bigger than a sugar cube. Moser designed the doghouse after learning a CAD design software program. She calls the whole unit “adorable.”

Magnetometers, big or small, are designed to perturb the surrounding magnetic field and then measure its behavior, which provides an indirect measurement of the overall background magnetic field.

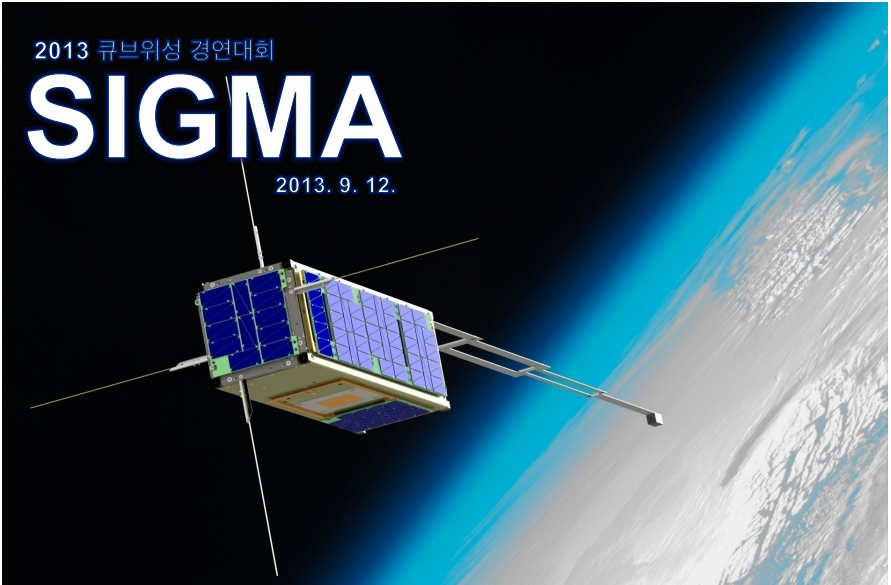

The 2x2x2 centimeter magnetometer Moser helped build will fly on an upcoming South Korean-led nanosatellite mission known as “Scientific cubesat with Instrument for Global Magnetic field and rAdiation”, or SIGMA. Principal investigators for the miniature magnetometer are Lessard and his former Ph.D. student Hyomin Kim, now a research scientist at Virginia Tech.

CubeSats are a new generation of pintsized satellites outfitted with modern, smart-phone-like electronics and tiny scientific instruments to, in effect, boldly go where bigger, more costly and complex satellite missions cannot. CubeSats hitch a ride into space on a rocket dedicated to a larger mission. They are placed into a compartment known as a Poly Picosatellite Orbital Deployer, P-POD for short, and jettisoned from the rocket at the proper orbital height above Earth.

SIGMA, slated for launch in late 2015, is a proof-of-concept mission and will represent the first CubeSat-borne science-grade miniature “fluxgate” magnetometer flown in space. A fluxgate magnetometer is more tolerant to radiation and more robust than other types of magnetometers, which also tend to be heavy and power-hungry, while the miniaturized version’s small size, low mass and very low power requirements allows it to fly on a 10x10x30 centimeter CubeSat. It is the lowest power fluxgate magnetometer Lessard is aware of.

“This whole effort was motivated by the fact that at the American Geophysical Union meeting a couple of years ago,” Lessard notes, “there was a lot of talk about CubeSats but nobody was talking about flying magnetometers on these missions because they’re big and bulky and suck up a huge amount of power.”

Shortly thereafter, Lessard was part of a successful grant awarded through NASA's Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research, or EPSCoR, Research Infrastructure Development (RID) program that, in part, funded initial research on the development of miniaturized instrumentation for magnetometers to be flown on CubeSats. Astrophysicist Toni Galvin of the SSC is the principal investigator on the EPSCoR grant and also directs the New Hampshire NASA EPSCoR program headquartered at UNH.

It is Lessard’s hope that, eventually, UNH will be able to build these miniature magnetometers for widespread use on space science missions.

“We hope to prove the technology of our magnetometer on this mission, and once we do, it opens the way for a possible future mission to the moon to measure magnetic anomalies using a CubeSat launched from a lunar orbiter. So this is a big thing as it may provide the opportunity for us to send one of our miniature fluxgate magnetometers to the moon.”

“Yeah, I get so excited about the lunar possibility, and so does Marc,” Moser says adding, “And I’m so excited, too, because this hasn’t been achieved before for this size magnetometer with its low power consumption and level of accuracy.”

Moser, of course, will be long gone from Lessard’s lab when that happens but she does plan to go to graduate school to study space science instrumentation. And while UNH with its long, proud history of building space instruments and flying on missions would be one of her first choices, she thinks it best to mix things up a bit and begin her graduate career at a different institution.

Doing what?

“Rovers or, and I know it’s a long shot, interplanetary space travel/human space flight,” Moser says. “I would like to be involved in building hardware and getting teams together. It’s so much fun being here at UNH and meeting so many different people with different interests. One of my roommates is in computer science, another is an electrical engineer and we’ll talk about same stuff I do but they having a completely different perspective on things, and that’s the best.”

Says Lessard, “For Chrystal, this has been a phenomenal ride I think. She came in and caught the wave and has been surfing like crazy ever since.”