Fall 2013

Earth Science

CALVIN DIESSNER'S master's degree work was launched in the basement of his parents' Dover, N.H. home after he received a 10-gallon aquarium for his sixth birthday. He tossed in some frogs and fish from a local pond and never looked back.

|

|

| Calvin Diessner. Photo by Kristi Donahue, UNH-EOS. |

Ten gallons soon became but a drop in the boy's ambitions and, over the years, the basement was transformed into a water world for assorted aquatic beasties.

"Every year I tried to get more tanks, and by the time I was 12 had about two dozen with fish and corals," says Diessner. "I can't tell you how much time I spent down there raising weird stuff—different aquatic plants and fish, trying to breed fish, shrimp, things like that. My parents were just exasperated."

But the exasperation was tempered with tolerance and had turned to pride by the time Diessner successfully defended his master's thesis last spring for a project that, you guessed it, involved fish swimming in tanks. Specifically, Diessner designed and built an experimental system where fish were grown in tandem with floating salad greens of bok choi and green bib lettuce. Such a system marries techniques of aquaculture and hydroponics to become "aquaponics."

|

|

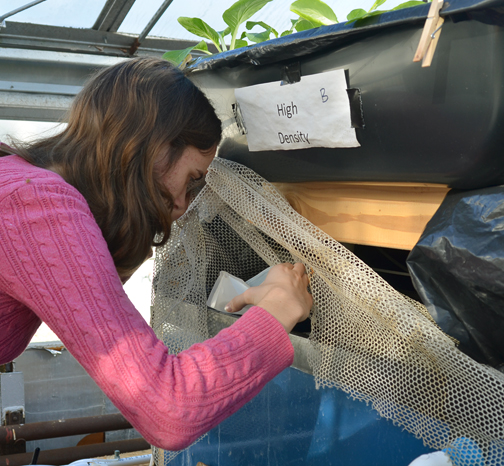

| Environmental engineering student Katie Taylor feeding fish as part of Diessner's aquaponics experiment. Photo by Kristi Donahue, UNH-EOS |

"My parents were always very supportive, even when I flooded their basement, but I don't think they ever thought my childhood hobby would manifest itself into a masters degree from UNH," Diessner says. "And I think what surprised them the most was not the fish, obviously, but the 'gardening' I did. They were pretty amazed at the size of my crops."

Indeed, so was Diessner's thesis advisor Barry Rock, a botanist and professor emeritus in the EOS Earth Systems Research Center.

"By the end of his first six-week trial run, it was amazing to see how robust the plants were in the high-fish density experiment, in which the fish waste supplied all the nutritional needs for the plants," Rock notes.

And therein lies the key to Diessner's success, because his aquaponics project was specifically designed to investigate how the waste from a specific fish species could be used as the primary fertilizer in a sustainable, self-regulating, closed-system.

Fertile ground

Conventional aquaponics is one technique in a system formally known as Integrated Multitrophic Aquaculture, or IMTA. In these systems, fish waste does provide nutrients necessary for plant growth, but current research suggests various essential nutrients are deficient when fish are fed standard commercial diets. The only nutrient input into these systems is the fish feed, which is precisely calibrated to a specific fish species' dietary requirements.

Notes Diessner, "Because of this, the fish feed typically lacks a wide range of nutrients required for continuous healthy plant growth. Mineral supplements in the form of granulated fertilizers are commonly used in research projects, and perhaps in the commercial market, too, and I suspect that these 'enriched' waters limit the fish species available for use in aquaponics."

Diessner's experimental approach was to grow both fish and plants in as sustainable and simple a fashion as possible. To do so, he chose a hardy, hybrid species of fish that, despite reports to the contrary, he hoped would thrive in such a system.

|

|

| Hybrid striped bass Photo by Kristi Donahue, UNH-EOS. |

Hybrid striped bass, also known as wiper or whiterock bass, are a cross between white and striped bass. The hybrid is more robust and adaptable than the parent species and can handle both salt and fresh water, high swings in temperature, are extremely resistant to disease, and are fast growing.

According to Diessner, the hybrid species got a bad rap as fish for aquaponics through no fault of its own. Rather, he says, "the majority of the reports on why they performed poorly were cases where people used the hybrids to grow things like tomatoes—a really complex plant that requires a great deal more nutrient input compared to lettuce. And when you fertilize the system that may limit the fish. In all likelihood it was the synthetic fertilizers that limited the success of the hybrid bass."

In his system, Diessner used no fertilizers and both fish and greens flourished. He hopes to publish his findings in the future for the good of the aquaponics cause—a cause he wants to continue being associated with.

From research to outreach

Specifically, he would like to help grow the field of aquaponics at the local level and as an all-natural, nonprofit, New England-based business venture. This future path is a bit surprising to even Diessner himself and was born, in part, out of his surprising response to the public outreach side of his master's work.

"I enjoyed the research but I don't know if that's necessarily the path I want to continue with. There were several periods during the two years of my project when I was able to talk to the general public about the experiment and aquaponics in general and I enjoyed that immensely—educating the public about this sustainable system and how they could potentially even do it at home."

Because his aquaponics system was set up at the UNH Macfarlane Greenhouses, Diessner had a big opportunity to interact and educate the public during Open House at Macfarlane.

"There were five to six hundred people who came to the greenhouse and saw the systems running, and in the last semester of my project I went to a handful of kindergarten and middle school classes and really enjoyed talking to the kids," he says. "The work was always so well received by people, which stimulated my interest in talking to the public more about this."

Further stimulus for the project was provided by Berlinsky's aquaculture students, twelve who ended up running the third trial of Diessner's experiment.

"They conducted the same experiments I did. It's rare as an undergraduate to get a whole semester's worth of experience doing a research project like this every day—testing water quality, feeding the fish in a prescribed way, monitoring the status of the plants, etcetera," Diessner says.

He adds, "The students got very excited about the project, and that was very gratifying for me, and it's another reason why I'd like to pursue this on the nonprofit level, bring it to the community, and get people involved in small-scale, hands-on sustainable food growing."

|

|

| Diessner's aquaponics experiment at the UNH Macfarlane Greenhouses. Photo by Kristi Donahue, UNH-EOS. |

Notes Berlinsky, "I think aquaponics has great potential as a sustainable food-producing system, and I hope to continue involving my students in this emerging research area."

Although at the moment Diessner is leaning towards continuing the work in the business and public outreach arena, he isn't ruling out further aquaponics research, ideally at UNH.

"If I could do that, I would most likely investigate the use of alternative fish feeds to remediate the nutrient deficiencies found in some plants grown in these systems," he says. "For example, what if we could feed fish a common insect that was grown off a vegetable diet high in some nutrient, like spinach, which is high in iron. Wouldn't be cool if that iron-enriched worm could reduce an iron deficiency in the system 'naturally'?"