Winter 2011

BACK IN 1998 at the National Science Foundation’s Summit Station Observatory in Greenland, a multi-institutional team of researchers led by atmospheric chemist Jack Dibb of the Complex Systems Research Center stumbled upon a surprising chemical process that subsequently launched an entirely new branch of scientific investigation – snow photochemistry.

Located at the peak of the Greenland ice cap, Summit is a pristine Arctic outpost and relatively free of local influences from pollutant chemicals. So when the scientists discovered the equivalent of urban air hovering above the snow they were baffled.

Expecting to find but scant amounts of nitrogen oxides, reactive gases which, among other things, play an important role in the formation of ground-level ozone or smog, they instead took readings eight meters (26 feet) above the snow that were surprisingly high and readings closer to the snow surface even higher. “Finally,” recalls Dibb, “we stuck the probe right into the snow and the numbers were astronomical.”

This discovery, and a similar, serendipitous find by a different team at the South Pole later that year, opened up the new avenue of scientific inquiry that seeks to understand the complex, small-scale chemical processes that occur when sunlight strikes the surface of snow.

“The whole issue wasn’t even on anybody’s radar screen before the late ‘90s. The thinking was that when it rained or snowed these reactive gases were taken out of the atmosphere and that was the end of the story,” says Dibb.

But obviously the story didn’t end there and the mystery has sparked ongoing and expanding investigation. Researchers are now trying to decipher what chemical compounds might be exerting an outside influence in the creation of these reactive gases that shouldn’t be there.

Specifically, scientists are measuring for ubiquitous halogen compounds, such as bromine, which they hypothesize may be a large player in the mismatch between modeled processes in the snow and processes that are measured.

To that end, Dibb will return to Summit in May to continue working on collaborative snow photochemistry research with Brown University and Georgia Tech scientists looking into how bromine may play a role in the recycling of nitrate – a precursor to the mysterious nitrogen oxide showing up in the snow.

Says Dibb, “Very small amounts of bromine in the atmosphere can really modify how the ozone chemistry works, how the nitrogen oxide chemistry works.”

Among other reasons, the work Dibb and colleagues are doing in the field of snow photochemistry is critical if scientists are to feel confident in their interpretation of ice core records. Notes Dibb, “Ice cores may be the best place to get past, atmospheric composition information but there are all these open questions about the accuracy, resolution, and fidelity with which snow records the composition of the air above it.”

The House that Jack Helped Build

Summit Station was the site of the Greenland Ice Sheet Project 2 (GISP2) beginning in 1989, and GISP2-related activities were eventually what took Dibb up to Summit after his arrival at UNH in 1988. But when the project hit bedrock in 1993 and closed operations, there was some question as to what the station’s future might hold.

Dibb was a key player in convincing the National Science Foundation to not only keep the lights on but to make Summit Station a year-round scientific observatory. “I helped convince NSF to let us keep doing projects after the drilling ended and to expand operations year-round as we had no idea of what was happening during the wintertime from a scientific perspective,” Dibb says.

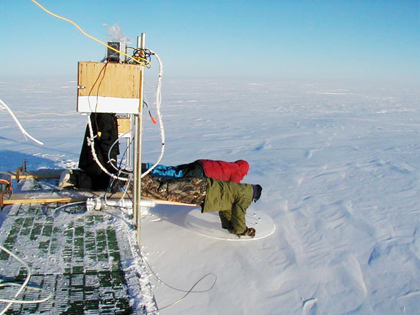

The effort was successful, and it was Dibb himself who tried the first year-round experiment in 1997. Today, there is a long-term commitment to keep Summit Station operating full-time as the only year-round, dedicated, staffed observatory in the high-altitude Arctic. The location is relatively free of local influences that could corrupt climatic records, and captures rare phenomena that can represent climatic trends and help scientists understand the impacts of climate change. The observatory is situated ideally for studies aimed at identifying and understanding long-range, intercontinental transport and its influences on air and snow chemistry and "albedo" or reflectivity.

|

|

| The Summit “berthing module” or sleeping quarters, which is the equivalent of three, combined office trailers with thickened walls to withstand the polar environment. Photo courtesy of John Burkhart. |

“So now Summit hosts one of six National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Global Atmospheric Baseline Observatories where NOAA can make the same suite of measurements of climatically relevant gases and aerosols at a select few places on the planet,” says Dibb. “This is a service they provide to the whole science community, especially modelers.”

The NOAA baseline stations are located strategically in an effort to get a global, average signal in both the northern and southern hemispheres. Explains Dibb, “So they’ve tried to locate their stations where there’s very little local influence. Barrow, Alaska, where they’ve been making observations for nearly half a century, used to be like that. But then the Prudhoe Bay oil fields went in and as more and more ice melts in the Arctic, and shipping, exploration, and drilling increases, the chances are good that Barrow is going to increasingly give you a regional signal.”

In addition to continuing his decades-long research efforts at the observatory, Dibb, along with CSRC’s Mark Twickler who heads up the NSF Science Coordination Office, are active in plans for the redevelopment of Summit Station, which will help it fulfill its mission as a sentinel, scientific outpost in a fast-changing Arctic landscape.